|

|

The Cyprus Conflict

The Main Narrative A narrative

is a descriptive account of what happened over a period of time. In any complex history,

there may be many competing narratives, and these will vary according to the competence, bias, resources or

goals of the narrator. Every historical document, even

scholarship, will suffer from some bias or incompleteness. In

Cyprus, each community has its own quasi-official narrative, relaying

and justifying its interpretation of events in the light of current

political discourse. These aspects of narratives are discussed elsewhere in this

site, in the section titled Historiography

& Nationalism.

CYPRUS by Keith Kyle Introduction Cyprus is an island of 3,572 square miles . . . in the eastern Mediterranean, of oblong shape parallel to the equator. It is 141 miles in length and at its widest point 59 miles in breadth. It is an island of mountains--the long narrow and elegant Kyrenia range that overshadows the inland capital of Nicosia runs just below the northern coastline; in the centre and west is the Troodos massif, including one of those heights which the Greeks named Olympus. Between these two is a plain, 12 to 15 miles wide, which is very fertile provided the rains arrive--which they sometimes do not. Scenery and climate alike seem to justify the classical reputation of Cyprus as the birthplace of Aphrodite, which explains the heavy dependence of the modern economy on the tourist industry. The northern shore faces Turkey, from which at the nearest point it is only 43 miles distant; Syria is 64 miles to the east, while the Greek mainland is 500 miles away. The great majority of the population is and has been for more than 3,000 years Greek by language and culture. Of a population estimated at independence at 556,000, excluding the British (most of whom would in future live within the Sovereign Bases), 80% were Greeks, whereas under 19% were Turks. By comparison the Roman Catholic minority in Northern Ireland is somewhere near 40%. The proportion of Turks to the total population of Cyprus is similar to that of the French Swiss in Switzerland or the Tamils in Sri Lanka and is rather smaller than the Protestant population would be in a united Ireland. But--and this point is vital to the whole story--the Turkish Cypriots were at the time of independence scattered over the whole island in no single sector of which did they form a numerical majority. Are we confronted here with a problem of minority rights? We have already touched the heart of the controversy: for it is the Turkish population's contention that it is not a minority but a separate and equal community; hence that the concept of minority rights offers no solution that is of interest to it. There was, when Cyprus achieved independence in August 1960, no Cypriot nation---nor much sign of one emerging, despite the common experience of British colonial rule which had left its mark on both communities and a common affection for the nature of the island. Greek and Turkish Cypriots had just emerged from a 'liberation struggle' in which they were on opposite sides. There was no university in Cyprus, no private business partnerships between Greeks and Turks, virtually no intermarriage. The one institution that was shared---the trade unions---had been substantially (though not entirely) torn apart by the pressures of the anti-colonial struggle.

After Cyprus became independent in August 1960, the period up till 1974 was

devoted to attempts to contrive some acceptable method of power-sharing that

would not involve such a traumatic upheaval which could in practice only be

undertaken by the exercise of physical force by the Turkish army. Since 1974,

when that force was employed, the unresolved task has been to arrive at some

tolerable accommodation to the results of its having been exercised. The Historical Background It is generally considered, as the result of excavations, that the Mycenaean Greek colonization of Cyprus took place towards the end of the second millennium B.C., when the indigenous population accepted Greek civilization and culture. During most of its recorded history Cyprus has been the object rather than the initiator of historic events. Part of the Assyrian empire and the Persian, it was picked up by Alexander the Great and then by Ptolemy. It became subject to Rome and afterwards to Constantinople. The (Greek Orthodox) Church of Cyprus is autocephalous (that is, independent of any Patriarch) on the grounds of its personal foundation by the Apostle Barnabas. Although this status was disputed it was upheld at the Council of Ephesus in 431 AD and subsequently in 498 by the Emperor Zeno after the bones of St Barnabas clutching a first edition of St Matthew's Gospel had been providentially discovered. Henceforth and to the present day the Primate--known since 688 as the Archbishop of Justiniana Nova and All Cyprus--is allowed imperial privileges: to hold a sceptre, wear the purple, and sign his name in red ink. Exceptionally, among Archbishops, he is addressed as 'Makariotatos' (Most Blessed). Byzantine rule over Cyprus was brought to an abrupt end in 1191 by Richard Coeur de Lion, who captured it in a fit of temper and later sold it to the Latin house of Lusignan. Under Latin rule the Greek Orthodox church was harshly subordinated to that of Rome; the Greek bishops (cut down from 14 to 4) had to do homage to those of Rome and were forced to live in remote villages. Possession of Cyprus passed in 1489 into the hands of Venice, which explains the presence of Othello on the island, and the Turks captured it from the Venetians in 1570-1. For the Greek Orthodox Church, Muslim rule meant liberation. The Latins were swept out and Muslims settled across the island principally on formerly Latin estates; many Latins and some Greeks allowed themselves to be converted to Islam. But the orthodox bishops were allowed to return to their sees, and, since the absence of an Archbishop was, according to Ottoman practice, bureaucratically irregular, one was hastily produced from Constantinople and recognized as Ethnarch, or spokesman for his people. Later, from about 1670 onwards, he was given the additional responsibility for imposing and raising taxes. This ensured the Church's pre-eminence among the Greeks of Cyprus. There was, nevertheless, a basic sense of insecurity in living under Turkish rule which periodically became justified. The Greek rebellion of 1821 in the mainland and in the Aegean islands, but not in Cyprus, began a century of bitter struggle between Greeks and Turks for the disentangling of the two cultures, religions and peoples which at that time were intermingled not only on the European mainland and the Mediterranean islands but also on the Asian mainland, where there were substantial Greek populations at Smyrna (now Izmir) and elsewhere. On Cyprus, which had not risen, the immediate Turkish reaction to the rebellion was to execute the Archbishop and his three episcopal brethren and some 500 prominent Greeks. The Kingdom of Greece, whose independence was recognized in 1832, was simply a core area of sovereignty, by no means including all the Greek territory on the European mainland and only a few of the Greek islands. Independence was therefore the beginning and not the end of the struggle for enosis, the Hellenic ideal of the coming together of all territory that was culturally Greek; the Greeks were henceforth actively concerned with collecting together the individual pieces of that empire. A second chunk of the mainland was added on in 1881. Britain had contributed in 1864 when Palmerston and Russell gave way to the demands for enosis in Britain's Greek empire, the Ionian islands including Corfu. Fourteen years later Cyprus fell into the hands of Britain. In 1878 at the time of the Congress of Berlin, Turkey, retaining nominal sovereignty, gave the island over to British administration as an assembly base for the rapid deployment force which Britain was supposed to have at the ready to deter further Russian penetration of the Ottoman Empire. Although there never in fact was such a force and Cyprus was not used for any military purpose until the Suez invasion of 1956, the idea that possession of the island was closely related to Turkey's strategic safety was firmly implanted in the Turkish mind. On the other hand, when the first British High Commissioner, Sir Garnet Wolseley, arrived at the Cypriot port of Larnaca, he was greeted by Kiprianos, Bishop of Kition, with the message: 'We accept the change of Government inasmuch as we trust that Great Britain will help Cyprus, as it did the Ionian islands, to be united with Mother Greece, with which it is nationally connected.' Every subsequent High Commissioner became accustomed to hearing the petition for enosis on ceremonial occasions. In 1912 the Greek Cypriot members of the Legislative Council resigned en bloc to campaign for this purpose. For a fleeting moment in 1915 Britain was willing to fulfill these hopes in return for a quick entry of Greece into the war; the offer was withdrawn when Greece declined. In the meanwhile Greece put together other Hellenic fragments. In a sequence of events that has not been far from the minds of both sides during the current Cyprus dispute, the Greeks in Crete, whose Turkish population (once in the majority) were still in the 19th century a larger minority than in Cyprus, rebelled against the Turkish rule in 1821, 1856, 1878, 1896 and 1897. There followed a succession of complicated and doomed constitutions, imposed by international intervention and intended to enable the two populations to live peaceably together under Ottoman sovereignty. After 1897 Crete was not off the international agenda till its final union with Greece in 1913 as a consequence of the Balkan Wars. The determination of the Turks that Cyprus should not be a similar story with a similar ending half a century later was to be a major factor in determining their policy. Under the Treaty of London in 1913 by which Greece acquired Crete, she also extended her mainland territory to the north and north-west and acquired Lemnos, Samos, and other Greek-speaking islands. In 1919, after Turkey's further defeat in the First World War, Greek troops were authorized by the allies to land on the Asiatic mainland at Smyrna, where there was a large Greek and Armenian population, a landing that was marked by the killing of some two to three hundred Turkish civilians. But the Greeks' ambitions had outstripped their strength. The 1921 war against Mustapha Kemal [Atatürk], with the Greeks marching into the Anatolian interior almost as far as Ankara, was a catastrophe for them, for the Greek and Armenian population in Asian Turkey, and for the city of Smyrna whose terrible destruction by fire and sword brought to an end the possibility of a Christian population in Asia Minor. By the Treaty of Lausanne (24 July 1923) a massive and compulsory exchange of populations was agreed, eliminating the Greeks from Asia and allowing them in Turkey to stay, with guaranteed minority rights, only in Constantinople (Istanbul) and a couple of islands. In compensation, the Turks were turned out of their homes in Crete and in the whole of Greece's territories except for Western Thrace, where they were promised similar minority rights. The financial settlement was not finally confirmed until 1930 when Venizelos and Atatürk, on behalf of the two countries and cultures, lavishly celebrated the end of a century of murderous feuding. Arnold Toynbee wrote in Chatham House's Annual Review for 1930 that 'this terrible process of segregation [of Greeks and Turks]---a process which had inflicted incalculable losses of life and wealth and happiness upon four successive generations of men, women and children in the Near East---had at last reached its term'. This was of course, with the exceptions noted, the abandonment rather than the celebration of the cause of minority rights. But Cyprus was left out of this grand reconciliation between old enemies

because, having been annexed by Britain in 1914 the moment Turkey came into the

war, it was not involved in the population exchanges. Indeed, as part of the

1923 Treaty of Lausanne, Turkey renounced forever any claim to sovereignty over

the island in favour of Britain. C

The Italian-ruled Dodecanese islands (including

Rhodes and Cos) were united with Greece as the result of the Second World War,

bringing Greek territory in the Eastern Aegean very close to a large part of the

Turkish coast. Greece felt herself as much an island nation as a mainland one,

thinking of the Aegean as her high street rather than as a waterway separating

her from Turkey. Meanwhile, however, the effect of Soviet pressure led both

Greece and Turkey to accept American assistance, and in 1951 to join NATO, thus

involving the armed forces of both in the structure of integrated command and

joint military exercises. Greeks came back to Izmir (Smyrna) for the first time

since 1922 as part of the joint NATO staff. The Decolonization of Cyprus: 'Never' At the end of the Second World War Britain came to realize that her European colony of Cyprus was politically among the most backward of her colonial territories. The Legislative Council had not met since 1931 when for the second time the Greek members walked out, whereupon a crowd shouting for enosis burnt Government House to the ground. Nor since that year had there been an Archbishop. First, two of the four bishops were deported from the island, on suspicion of fomenting the unrest; then immediately afterwards the incumbent Archbishop died and the one remaining bishop declined to organize the election of a successor. (There is still in the Church of Cyprus a process of indirect election largely by the laity, as in the earliest Christian churches). The press was censored, political parties forbidden, the flying of the Greek flag prohibited by law. In these circumstances the trade unions emerged as the principal element of opposition to the colonial establishment and the only one to cross communal lines. When in 1941 political parties had been allowed again, it was not surprising that the first one to be formed, AKEL, sprang from the union movement. Its original leaders spanned the political spectrum but before long it came under communist control. Sixty years of British rule had done nothing to encourage the emergence of a Cypriot nation, though to be sure the Greek and Turkish Cypriots alike displayed the marks of British law and administration. To a certain degree the two communities had been played off against each other. So long as there was a Legislative Council British Governors relied on the votes of the Turkish Cypriot members to block periodic bursts of Greek Cypriot political activism. Greek and Turkish schools largely looked to their respective 'mother countries' for inspiration and in many cases for staff, though the Greek connection was the more active of the two. For Turkish Cypriots the 1931 crisis had been a revelation of the Greek Cypriots' continued devotion to union with Greece; it guaranteed the Turks' alignment with the colonial power even though their own political expression was as much denied to them as was the Greeks'. Both kinds of Cypriot were to be found among the leaders and members of the Pan-Cyprian Federation of Labour (PEO). A wealthy Turkish Cypriot was likely to be a landowner (often absentee); the role of the bourgeoisie was filled almost exclusively by Greek Cypriots. There were Turkish quarters in all the main towns, and of the villages in 1960, 114 or about 18% were mixed (though this was only a third of the number seventy years before). Even in the mixed villages, however, it was possible to tell which was the Greek and which the Turkish part. There were 392 purely Greek and 123 purely Turkish villages but typically they were to be found cheek-by-jowl with villages of the opposite community. This was so in each of the island's administrative districts, although not many Turkish Cypriots were to be found in the Troodos mountains. The anthropologist Peter Loizos has pointed out [in a 1976 MRG report on Cyprus] that most Cypriots had for most of the time been able to live close to the members of the opposite community without friction: Very few of them have intermarried and this is normally frowned on by both sides. But they have had both some social relations and economic cooperation and, although there has been consciousness of difference and sometimes antagonism and mistrust, the ordinary people have never found it hard to "live together", i.e. to share the island, villages, suburbs, coffee-shops and wedding festivities. Unfortunately, the world is full of examples (Northern Ireland being one) where the existence of this degree of social toleration under one set of circumstances will offer little safeguard when the circumstances change. The opposition to British colonial rule and to all British proposals for

self-government was led by two men, Michael Mouskos, who in October l950, at the

age of 37, was elected Archbishop of Nova Justiniana and All Cyprus taking the

title of Makarios ('Blessed') III, and Colonel George Grivas, a Cyprus-born

Greek officer who had headed an extreme right-wing guerrilla group during the

Axis [Nazi] occupation of Greece [during the Second World War]. Three years before

Makarios's election the British had permitted the bishops to return, whereupon,

to the alarm of most Orthodox leaders, the When the British proposed a first-stage form of self-government (the Winster constitution) the right and the Church would not talk because it was not enosis; the left would talk but demanded for a European island with well-qualified professional cadres something more advanced. This being the period of the Greek civil war the British, who were in any case being criticized for allowing too much freedom to communists, were not prepared to yield more to the left. Up to this point, the Turkish Cypriots, who until about this time were normally referred to as the Muslims, had not figured at all prominently in discussions about Cyprus. Being a rather stagnant society they did not make their point of view well known. Nor was it actively pressed by Turkey though representations were made in 1948 and there was one robust official declaration of interest in 1951. It is the Greek and Greek Cypriot thesis, from which nothing will move them, that Turkish interest and involvement, which would otherwise have remained quiescent, was fomented by the British, especially by Anthony Eden. One must say straightaway that there was a motive. The British had decided that they would have to leave the Suez Canal and were now planning to transfer the whole panoply of their Middle East Command to Cyprus, thus for the first time giving it the military significance it was supposed to have in 1878. C Nevertheless the Greek assumption that with British goodwill the island could have been swiftly transferred, complete with sleeping Turks, to Greek rule without serious conflict may well be questioned. It does not follow from the fact that Britain's two reasons for staying--strategic and the need to avoid stirring up Greco-Turkish hostility--were mutually supporting, that one of them had to be bogus. After all, Greece and Turkey were both military allies of Britain and of each other. On 28 July 1954 the Minister of State for the Colonies, Henry Hopkinson, replied to a debate about Cyprus with an ineptitude that came oddly in a former professional diplomat, that there were certain territories in the Commonwealth 'which, owing to their particular circumstances, can never expect to be fully independent'. After adding mysteriously that he would not go as far as that about Cyprus, he then promptly did go that far by recalling that he had already said 'that the question of the abrogation of British sovereignty cannot arise--that British sovereignty will remain.' C Greece then, for the first time, tried to internationalize the dispute by bringing it before the United Nations General Assembly as a simple case of self-determination. Thanks to British and American influence she did not on this occasion get much change and the debate provided the occasion for Turkey to declare that Cyprus had never belonged to Greece, historically its people were not Greek, and geographically it was an extension of Anatolia. They would not, said the Turks, accept any change in the status of the island that had not received Turkey's wholehearted consent. These Turkish arguments had an anachronistic sound in an era when first priority is supposed to be given to the views of the people concerned. After all, if people thought they were Greeks, then Greeks they were--and in any case past relationship to a kingdom that had only existed since 1832 could have no meaning. The relevant issue was the position of the Turkish Cypriot community and how much, if at all, the weight to be attached to that community of less than 20% of the total population should be boosted by Cyprus's geopolitical location--near Turkey and far from Greece. The main UN reaction (in the age of Western domination of that body) was one of horror at the sample of the Greco-Turkish polemic that threatened in the event of the Cyprus issue being fully discussed. In the autumn of 1954 the Greek prime minister, Field Marshal Papagos, who

had been personally offended by Eden's dismissive treatment of the case for

enosis (in a conversation in Athens in September 1953), and Archbishop Makarios

both gave the go-ahead to Grivas who, in hiding in Cyprus, had called his

underground organization EOKA (Ethniki Organosis Kyprion Agoniston,

National Organization of Freedom Fighters) and himself 'Dighenis' to launch a

campaign of sabotage. On 1 April 1955 the transmitters of the Cyprus

Broadcasting Station were blown up and a series of simultaneous, but less

effective, explosions took place across the island. The revolt had

begun*. British attempts at a solution The Cyprus problem could either be tackled domestically--that is, as between Britain and her colonial subjects, or internationally. And, if internationally, a solution might be attempted between Britain and Greece or at a three-power level (Britain, Greece and Turkey); at a NATO level which would include particularly the United States and the Secretary-General of NATO (at first Lord Ismay but later Paul-Henri Spaak); and at the level of the United Nations, where the diplomacy was essentially of a declaratory nature. The domestic politics of Greece, Turkey and Britain (in which a section of the Labour party, led by Barbara Castle, was markedly pro-Greek Cypriot) at various times obtruded. There was a basic absence of understanding between the British and the Greek Cypriots in their analysis of the political problem. The latter, and especially the Orthodox church, identified themselves with the whole island, and thought of the dispute with Britain as a classic anti-colonial one in which complications about the Turks were only a British excuse. Greek Cypriots simply did not take seriously warnings about the likely reaction of the Turkish Cypriots to any change of sovereignty, and felt--and retrospectively still feel--that it was unnecessary for Britain in the circumstances of the 1950s to do so. The Turks themselves did not take seriously the possibility of Britain yielding to such a demand. It is correct that Britain alerted them not to count on this too complacently. Anthony Eden states in his memoirs that he minuted a telegram in July 1955 that it was as well that Turks should speak out 'because it was the truth that the Turks would never let the Greeks have Cyprus'. This could be interpreted as inciting the Turks, but it could also be considered a prudent precaution against Greek overconfidence. However one decides to interpret this, Eden chose the tripartite route. A conference of the three allies was convened in London for the end of August 1955 at which Harold Macmillan, then Foreign Secretary, proposed that the problem of self-determination (by now the code-word for enosis) be left to one side and that Cyprus should receive self-government by stages at the end of which the Governor would control only foreign affairs, defence and public security. The Turks would have a share of ministerial portfolios and Assembly seats proportionate to their share of the population and there would be a tripartite (British-Greek-Turkish) committee that would supervise the arrangements both for transferring power and for guaranteeing minority rights. The initiative was a failure: Greece would not accept anything which disregarded the issue of self-determination; Turkey would not accept anything that did not explicitly renounce it. Macmillan later admitted [in his memoir, Tides of Fortune] that 'it could not be denied that the conference had perhaps increased rather than lowered tension'. While this conference was going on there was an alarming burst of anti-Greek rioting and demonstrations in Istanbul, probably stage-managed in the first instance but running rapidly out of control. The targets were the Greek merchants and the Greek Orthodox church while the Turkish press was full of stories which complained of the treatment of the Muslims in Western Thrace. No effort seemed to have been made by Turkish police to protect the pillaged churches and shops, and 29 out of 80 Greek Orthodox churches, 4000 shops and 2000 homes in Istanbul were completely destroyed. The message was clearly meant to be that Turkish forbearance was not to be too much counted on. As the EOKA revolt gathered momentum and casualties on both sides mounted, Britain tried to escape from the box of 'never'. Field Marshal Harding, who had been sent out as Governor, bore with him a painstakingly crafted formula, explaining that whereas self-determination was not on at the moment for strategic reasons and 'on account of the consequences on the relations between NATO Powers in the Eastern Mediterranean' the situation might change if self-government showed itself in practice to be 'capable of safeguarding the interests of all sections of the community'. A constitutional commissioner from Britain was to recommend how this might be done. After agonized debates in the Ethnarchy Council, Archbishop Makarios for the first time agreed to negotiate but on three conditions: the Governor's reserve powers were not to include internal security; the Turkish minority's rights were to be confined to religion and education; and there was to be an immediate general amnesty. Grivas, anxious to sabotage any negotiations at all, ended any chances of agreement by a series of massive explosions in Nicosia as the Colonial Secretary arrived. The British deported Archbishop Makarios and his more intransigent enemy, the Bishop of Kyrenia, to the Seychelles (where they were kept for a year and then allowed to return to Europe but not Cyprus) but pressed ahead with the Constitutional Commissioner, Lord Radcliffe. Radcliffe abandoned any suggestion of a handing over of functions by stages because of the 'adult people' he found on Cyprus. Bearing in mind his terms of reference which required that foreign affairs, defence and internal security were to remain with the Governor, Cyprus should have maximum self-government at once. Radcliffe completely rejected the case which the Turkish Cypriots, led by a physician, Dr Fazil Küçük, advanced for equal representation of Greek and Turkish Cypriots in the legislative assembly. This, [Radcliffe] declared, could only be justified in the case of a federation for which there was no basis either territorially or in the numerical balance of the population. Guarantees of minority rights were appropriate to the Turkish case, with a Turkish Cypriot minister and 6 reserved places in the legislature and reinforced access to the courts in case of allegations of administrative or legal discrimination. C In a way the bargain offered to the Greek Cypriots was a very good one, especially as the Governor's powers were in practice likely to dwindle once the Greek Cypriot majority had effectively taken over the Government. Some retrospectively regret the way in which it was immediately rejected. But Archbishop Makarios was not returned and the Colonial Secretary, in presenting the Radcliffe Report to Parliament made the classic blunder of stating that if the time ever came at which it would be possible to grant self-determination it should be granted to both communities. A veteran Turkish diplomat, looking back over the 'enormous and patient work' required to secure Turkey a 'right of say' in Cyprus, described this British statement as 'in a way, a road leading to taksim' (i.e. partition). Taksim became the slogan which was used by the increasingly militant Turkish Cypriots to counter the Greek cry of 'enosis'. In 1957 Küçük declared during a visit to Ankara that Turkey would claim the northern half of the island. The Turkish Cypriots were therefore already discussing during British rule and under the pressures of the EOKA revolt, solutions--federation and partition--which logically would require an exchange of populations on, proportionately, an immense scale (for example, the movement of more Greek Cypriots than the entire Turkish Cypriot population) to make them feasible. At first they were merely calling attention to the kinds of unwelcome issues that might be raised by the majority's persistent cry for self-determination. But as Grivas went ahead with his campaign, accompanying EOKA acts of violence against the British and their Greek Cypriot collaborators with civil disobedience by sections of the community (especially schoolchildren), economic boycott of British goods and services, and acts of ruthless coercion against those Greek Cypriots--especially the communists in AKEL and the trade unions--who did not wish to cooperate, the British fell back more and more for support on the Turkish community. They used the Turkish Cypriots to build up the police and the special constabulary and to form a mobile reserve. This created hostility between the two communities; when a Turkish policeman was killed by EOKA the Greeks saw a policeman fall, the Turks saw a Turk. In January 1957, for instance, a Turkish Cypriot auxiliary was killed and three wounded by a bomb when guarding a power station; a Turkish Cypriot crowd smashed a number of Greek shops. Ten days later there was similar trouble in Famagusta. On 27 and 28 January 1958, there were two days of serious rioting by thousands of Turkish Cypriots in Nicosia leading to pitched battles with British forces at the end of which seven Turks were dead. This was a clear sign of the rise of a Turkish para-military organization, the TMT (Turk Mudafa Teskilat-- Turkish Defence Organization) and the loss of confidence by the Turkish Cypriots in the durability of Britain's stand against the Greeks. The cell structure of EOKA was copied by Rauf Denktash, one of the TMT's founders, who went to Turkey to obtain the assistance of the Turkish Government and Army with training and weapons. Also, like EOKA, the TMT was strongly anti-communist and brought intense pressure to bear on Turkish Cypriot members of left-wing unions and clubs. Premises were burnt down, some left- wing Turkish personalities were killed, hundreds of Turkish Cypriot members of the communist-led PEO (Pan-Cyprian Federation of Labour) felt it necessary to leave and were in fact advised to do so for their own safety by their Greek Cypriot comrades. C Demands began to be heard for the establishment of a Turkish army base on Cyprus. On 7 June 1958, following a bomb explosion outside the Turkish press office

in Nicosia, there was an immediate invasion by Turkish rioters of the Greek

sector, and Greek Cypriot residents were expelled from a mixed district.

Communal clashes followed in the rural areas between neighbouring Greek and

Turkish villagers armed with knives, sticks and stones, in the worst of which a

group of Greeks just released from arrest by the British were murdered at

Geunyeli. Grivas was known to be organizing Greek villagers against expected

Turkish attacks and making plans for reprisals. The new Turkish militancy was

also apparent in Istanbul where demonstrations in the summer of 1958 were held

against the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Movements northward from Turkish Cypriot

villages in the south, most of them spontaneous, some organized by TMT, were

taken as clearing the ground for partition. In July Grivas ordered raids on

police stations with Turkish policemen as chief targets, and waived all

restrictions on killing Turks. Many Turkish villages were burned. But in August

an intercommunal cease-fire was proclaimed and held. Meanwhile in London, Harold Macmillan, by now Prime Minister, had reassessed

British strategic requirements in the eastern Mediterranean. 'I am not

persuaded', he wrote on 15 March 1957, 'that we need more than an airfield on

long lease or in sovereignty. Then the Turks and the Greeks could divide the

rest of the island between them.' In 1958 he asked the Secretary-General of NATO

to act as conciliator. In the summer Archbishop Makarios indicated for the first

time that he would accept independence for Cyprus rather than union with Greece;

he had been persuaded that Macmillan would otherwise go through successfully

with his threat of partition or, at the very least, establish Turkey in a

position on the island from which it would be impossible subsequently to

dislodge her. Responding to these developments Greece and Turkey entered into

direct talks which produced the Zurich Agreement followed immediately by the

Lancaster House settlement between them and Britain, both in February 1959.

Although Makarios and a very large delegation from Cyprus were present in London

and although in the end he felt obliged to accept the terms, this was a solution

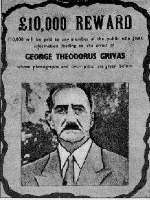

imposed from outside Cyprus by the three interested powers. Top photo: Rauf Denktash, longtime Turkish Cypriot leader, in front of a flag of Turkey; © Jérôme Brézillon/Métis, from Revue Middle photo: Archbishop Makarios Bottom photo: George Grivas in a British "wanted" poster, offering 10,000 pounds for his capture |

|

There are basically three types of political solution that are available for

this type of plural society and all three have been proposed for Cyprus. There

is, first of all, the classic regime of guaranteed rights for the minority--rights

over religious observance, education, use of language in schools, in law courts,

in communications with government, in broadcasting---probably with at least one

minister charged with protecting minority rights, and a few seats in the

legislature. Apart from these special rights, normal rule by democratic majority

prevails. Such was the system proposed under the British by the Radcliffe

report---though, to be sure, sovereignty and powers over certain matters were

reserved to the British. The second type has been called the consociational

system, or power-sharing, when for a distinct range of matters the

communities are treated as units within which decisions may be arrived at

democratically but between which they can only be made through consensus,

forbearance, deals. The Government under such a scheme is a compulsory coalition

between the leaders of the different communities. Consociation is a

constitutional method which is usually extremely complicated in description,

depending as it does on a series of checks and balances; it depends for its

success on the willingness of the participants to accommodate each other in

practice once the nature of the game comes to be understood and accepted as

being at least the lesser of the evils available. Such was the 1960 constitution

drawn up for Cyprus. Finally there is federation, which requires a

sufficient physical separation of the communities to ensure that each of them is

dominant in at least one federated unit. Given the demographic situation in

Cyprus this was impractical---short of a really drastic transfer of populations

of the kind that had happened between Greece and Turkey in the 1920s and in East

and Central Europe at the end of the Second World War.

There are basically three types of political solution that are available for

this type of plural society and all three have been proposed for Cyprus. There

is, first of all, the classic regime of guaranteed rights for the minority--rights

over religious observance, education, use of language in schools, in law courts,

in communications with government, in broadcasting---probably with at least one

minister charged with protecting minority rights, and a few seats in the

legislature. Apart from these special rights, normal rule by democratic majority

prevails. Such was the system proposed under the British by the Radcliffe

report---though, to be sure, sovereignty and powers over certain matters were

reserved to the British. The second type has been called the consociational

system, or power-sharing, when for a distinct range of matters the

communities are treated as units within which decisions may be arrived at

democratically but between which they can only be made through consensus,

forbearance, deals. The Government under such a scheme is a compulsory coalition

between the leaders of the different communities. Consociation is a

constitutional method which is usually extremely complicated in description,

depending as it does on a series of checks and balances; it depends for its

success on the willingness of the participants to accommodate each other in

practice once the nature of the game comes to be understood and accepted as

being at least the lesser of the evils available. Such was the 1960 constitution

drawn up for Cyprus. Finally there is federation, which requires a

sufficient physical separation of the communities to ensure that each of them is

dominant in at least one federated unit. Given the demographic situation in

Cyprus this was impractical---short of a really drastic transfer of populations

of the kind that had happened between Greece and Turkey in the 1920s and in East

and Central Europe at the end of the Second World War. communists in AKEL, being the most

efficient politicians, organized the election of an Archbishop, who died early.

As it happened there were three such elections in as many years; and, already by

the time of the second, AKEL's opponents had recaptured the machinery of

election and the political leadership of the Greek community. AKEL's idea of

petitioning the United Nations against colonial rule was taken over by Makarios,

already a bishop, who at the beginning of 1950 organized a plebiscite campaign

through the machinery of the Orthodox Church which produced a 96% vote in favour

of union with Greece. In the following October, when he was elected Archbishop,

he declared that 'no offer of a constitution or any other compromise will be

accepted by the people of Cyprus'. Colonel Grivas, though an obsessional

anti-communist, decided that violence was necessary against the British to

dislodge them from Cyprus and began preparing for the day. He expounded his

ideas to Makarios, who was at first sceptical and insisted that in any case the

colonel should think in terms of sabotage

communists in AKEL, being the most

efficient politicians, organized the election of an Archbishop, who died early.

As it happened there were three such elections in as many years; and, already by

the time of the second, AKEL's opponents had recaptured the machinery of

election and the political leadership of the Greek community. AKEL's idea of

petitioning the United Nations against colonial rule was taken over by Makarios,

already a bishop, who at the beginning of 1950 organized a plebiscite campaign

through the machinery of the Orthodox Church which produced a 96% vote in favour

of union with Greece. In the following October, when he was elected Archbishop,

he declared that 'no offer of a constitution or any other compromise will be

accepted by the people of Cyprus'. Colonel Grivas, though an obsessional

anti-communist, decided that violence was necessary against the British to

dislodge them from Cyprus and began preparing for the day. He expounded his

ideas to Makarios, who was at first sceptical and insisted that in any case the

colonel should think in terms of sabotage  rather than of guerrilla warfare.

rather than of guerrilla warfare.