|

|

Several landmark Center lawsuits have gone to the U.S. Supreme Court. Center legal counsel Richard Cohen talks to reporters during the state trooper case.

(special) |

|

By the late 1960s, the legislative victories of the Civil Rights Movement had yet to be tested. In Montgomery, Alabama, the Movement's birthplace, two Southern lawyers committed to racial equality were determined to exercise these laws to their fullest potential.

By taking pro bono cases that few others would pursue, Morris Dees and Joseph J. Levin, Jr. helped implement the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Some of their early lawsuits resulted in the desegregation of recreational facilities, the reapportionment of the Alabama legislature and the integration of the Alabama State Troopers.

After formally incorporating the Southern Poverty Law Center in 1971, with Julian Bond as its first president, Dees and Levin began seeking nationwide support. They mailed thousands of letters explaining their clients' needs and received donations from committed activists all over the country, enabling them to hire a staff and expand their work for justice.

During the 1970s and '80s, the Center's courtroom challenges led to the end of many discriminatory practices. Their cases won equal benefits for women in the armed forces, ended involuntary sterilization of women on welfare, and reformed prison and mental health conditions. Several of these early cases resulted in landmark decisions in the U.S. Supreme Court.

|

|

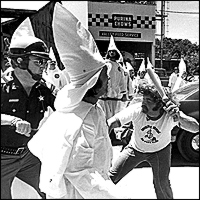

Klan violence in the late 1970s prompted the Southern Poverty Law Center to begin monitoring organized hate activity.

(Chris Bell) |

|

Combating the Klan

When Klansmen in Decatur, Alabama, attacked a civil rights gathering on May 26, 1979, the Southern Poverty Law Center brought its first civil suit against a major Klan organization. That case led to the 1981 creation of Klanwatch to monitor organized hate activity across the country. When the scope of this work broadened, it was renamed Intelligence Project.

SPLC attorneys developed strategies to hold white supremacist leaders accountable for their followers' violence. Suing for monetary damages for victims of Klan violence, the Southern Poverty Law Center was able to bankrupt several major Klan organizations and to draw national attention to the growing threat of white supremacist activity.

SPLC civil suits would eventually result in judgments against 46 individuals and nine major white supremacist organizations for their roles in hate crimes. Multimillion-dollar judgments against the United Klans of America and the neo-Nazi Aryan Nations effectively put those organizations out of business. Other suits halted harassment of Vietnamese fishermen in Texas by the Knights of the KKK and paramilitary training by the White Patriot Party in North Carolina.

In 1994, the Southern Poverty Law Center began to investigate white supremacist activity within the antigovernment militia movement. Shortly before the April 1995 Oklahoma City bombing that took the lives of 169 people, Morris Dees wrote a letter warning U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno of the danger posed by militias.

|

|

Center researchers daily track racist websites.

(Daemon Baizan) |

|

After the bombing, the Southern Poverty Law Center published critical information and special reports about the growth of the militia movement and called for increased law enforcement. As the 1990s ended, the numbers of antigovernment groups waned. At the same time, the Intelligence Project's monitoring efforts expanded to include groups such as the Nation of Islam, the Council of Conservative Citizens and the League of the South.

As the white supremacist movement grew more sophisticated – its members trained in the use of weapons and organized into secret cells – the data compiled by the Intelligence Project became even more important to law enforcement.

Today, its quarterly Intelligence Report is read by nearly 60,000 law enforcement officers nationwide, and Intelligence Project research has led to criminal convictions in several hate crime cases.

When the Southern Poverty Law Center began taking on the Klan in court, threats of retaliation against the SPLC became real. Klansmen burned the Southern Poverty Law Center's office in 1983. Over the years, several plots to bomb the SPLC offices and kill Morris Dees were thwarted.

|

|

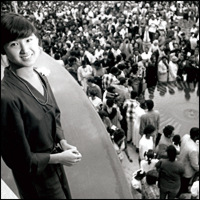

Civil Rights Memorial designer Maya Lin at 1989 dedication ceremony.

(Thomas England) |

|

The Next Generation

SPLC lawsuits were effective in weakening organized white supremacist activity, but random hate crime was increasing in the 1980s. Children were growing up with little knowledge of the sacrifices that were made to bring legal apartheid to an end. In 1989, the Southern Poverty Law Center decided to memorialize those killed during the Civil Rights Movement and to make the stories of their lives accessible to all who seek to learn more about that era.

Maya Lin, designer of the Vietnam War Memorial, was commissioned to design the Civil Rights Memorial. It stands on a plaza facing the Southern Poverty Law Center in Montgomery, drawing visitors from countries around the world.

In 1991, the Southern Poverty Law Center launched Teaching Tolerance, to provide teachers with free classroom materials on tolerance and diversity. The program's award-winning magazine is now read by more than 600,000 educators nationwide, and Teaching Tolerance multimedia kits are in use in thousands of schools across the country.

National Attention

Though vilified by extremists, the Southern Poverty Law Center's work has also earned widespread acclaim.

|

|

SPLC founder Morris Dees (right) accepts the National Education Association's top award from NEA president Bob Chase.

(special) |

|

Organizations such as the American Bar Association, the National Education Association, the American Civil Liberties Union, the NAACP, the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith, and the Friends of the United Nations recognized the Center as a leader in anti-bias litigation and education. President Clinton's Initiative on Race cited the Center's tolerance education work as a national model.

There is no doubt the Center's work will still be needed in years to come. As America grows more diverse, the Center will continue to promote and protect our nation's most cherished democratic ideals.

|