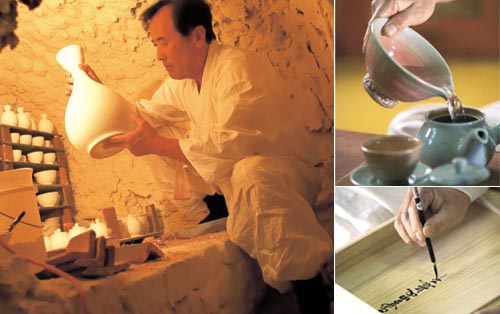

It's three in the morning and the "mangdaengi" (pottery kiln) is already lit.

"Now," says Kim Jeong-ok, 67, the master potter, after watching the fire inside a small domed tunnel connected to mushroom-shaped clay bricks. His son, Kyung-shik, 39, hurriedly shovels the logs to add more strength to the flames.

The process repeats for the next 14 hours to keep the temperature above 1,300 degree Celsius. It's the only way to "encounter the treasure” says the old potter. The kiln can produce about 150- 200 pieces of pottery at once this way, but only about five percent can be called a masterpiece. The price? Some have a set cost while others are open to discussion with the potter himself.

Kim Jeong-ok, also known by his artisitc name Baeksan (White Mountain) is Korea's only sagijang (master potter), designated Intangible Culture Property No.105 -- a living human treasure. His family has been potters for seven generations, a legacy Kim hopes to pass on to his only son down the road.

While some of Kim's works are worth over 100 million won and his skills are praised both at home and abroad, pottery did not always look like a promising field. He was forced to give up school during middle school to help his father, and even then, the family could not earn enough to get by. His father, although a skilled potter himself, saw demand dry up as the country became embroiled in war and people's tastes shfted to cheap utensils made of galvanized iron and colorful western dishes. Back then, Kim even saw grass growing next to the mostly dormant kiln.

Nonetheless, Kim hung on to his life as a potter, but more out of desperation than a sense of duty to maintain the 200-year-old family tradition. But looking back, he wonders if some kind of destiny was at work.

"Were it not for my grandfather Kim Un-he who was recruited as a potter for the royal palace and were it not for my father Kim Gyo-soo who didn't abandon the kiln during the war, there wouldn't be any of my works from the mangdaengi kiln," he said.

The 1843 kiln is now considered the oldest surviving kiln in Korea -- the others having been destroyed by the forces of foreign armies or rapid industrialization. But the fire-tested bricks were not the only thing to survive those harsh times.

"Amid the Korean War, only our Chongho White ware was able to continue its roots. Other porcelain brands, including Buncheong earthenware ceased to be. That's because my grandfather, my father and I never give up," Kim said.

"Life was hard until the mid-60s when my pottery gained popularity among Japanese tourists. Although the place I live in was reputed as a perfect spot to make pottery -- with good soil, water and abundant lumber -- there wasn't adequate transportation to deliver those materials. I had to carry everything on my back down from the mountain. When you walk for miles carrying sand you'd sometimes notice a small pool of water forming within the wet sand. It still gives me shivers thinking of that."

It was only after Kim reached his forties that the country started acknowledging his talent. Starting with his winning the Critic's Choice Award at the Gyeongbuk Artifacts Competition in 1983, he began to sweep pottery competitions. He won the National Folk Craft Show's Special Prize in both 1988 and 1989 and in 1991 proved himself the best in the ceramic world after reviving the "Jeongho Dawan" otherwise known as the "Ido tea bowl" from the old Joseon Dynasty. The original cup taken to Japan during the Imjin War (1592-1598) has been preserved as a national treasure of Japan ever since. In 1996, he won the title "Sajijang", or "Master Potter."

While some critics comment that his works are somewhat "feminine," they also exude a sense of simplicity and calm beauty. In the case of the light-yellow jeongho dawan made from sandy soil, one tea bowl expert praised its "special balance that gives off a feeing much grander than the actual size." The traces of finger prints within the cup made during its spinning resembles the winding joint of bamboo trees.

His pieces are in the permanent exhibitions of some of the world's most prestigious museums such as the Smithsonian Institution in Washington D.C., The Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, Canada, and The Museum of East Asian Art in Berlin. Even the Dalai Lama was delighted by his art work. The master potter receives the royal treatment whenever he visits Japan, ushered to a better seat than the mayor's.

Of the 23 potters in Mungyeong, three are among the nation's five best, including Kim. The other two are titled "myeongjang" or "master artist." These Mungyeong potters no longer have to worry about lugging tons of clay down from the mountain or wondering around the woods for the best trees, but they still insist on doing things the old way.

Kim for one, still uses his family's 240-year-old potter's wheel and chooses logs from the red pine for its superior flames. That's the only way to reproduce the masterpieces of old times, he explains.

"People ask over and over why I even bother reviving the old wares. So I tell them over and over, 'It's something that only I, as a Korean, can do, not an Englishman or German. These are our own masterpieces and no one can recreate them for us.'"