|

|

Editors: Managing Editor: Editorial Assistant: Contents Info |

Volume 5, Number 1, January - March 2001

Vaginal Neoplasia in a Male-to-Female Transsexual: Case Report, Review of the Literature, and Recommendations for Cytological Screening

Citation: Lawrence A. (2001) Vaginal Neoplasia in a Male-to-Female Transsexual: Case Report, Review of the Literature, and Recommendations for Cytological Screening. IJT 5,1, http://www.symposion.com/ijt/ijtvo05no01_01.htm

A case of intraepithelial neoplasia (carcinoma in situ) of the

neovagina in a male-to-female (MtF) transsexual is presented. Vaginal

carcinoma is rare in natal women, including those who have undergone

vaginoplasty for vaginal atresia. Vaginal cytology examinations (Pap

smears) are not recommended following hysterectomy for benign disease;

they probably have limited value following vaginoplasty for benign

conditions as well. MtF transsexuals should receive annual pelvic

examinations following vaginoplasty, but there no evidence to suggest that

they would benefit from vaginal cytological screening in most cases.

However, if the glans penis has been retained as a neocervix, cytological

examination of the neocervix is a reasonable practice.

By conservative estimate, some 10,000 male-to-female (MtF) transsexuals have undergone vaginoplasty. However, there is no consensus as to whether such patients should undergo routine cytological (Pap smear) screening for cancer of the neovagina.

The Standards of Care for Gender Identity Disorders state that gender patients "should be screened for pelvic malignancies as are other persons." (Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association, 1998). In natal women who have undergone hysterectomy for benign disease and thus lack a cervix, vaginal cytological screening has been recommended only every ten years (Piscitelli et al, 1995), or not at all (Canadian Task Force on Cervical Cancer Screening Programs, 1982; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 1996; Pearce et al, 1996; Fetters et al, 1996; Noller, 1996). Presumably these recommendations would also apply to MtF transsexuals. Yet, at least one author has suggested that MtF transsexuals need a "full evaluation with a Pap smear" annually, "because of occasional reports in the medical literature of vaginal cancer in the post-op woman." (Kirk, 1999).

This paper presents the first published case report of carcinoma in situ

of the neovagina in a MtF transsexual. It also reviews related cases, and

considers circumstances that might justify more frequent cytological

screening in MtF transsexuals than in natal women.

A 36-year-old MtF transsexual underwent sex reassignment surgery in 1992. A standard penile inversion vaginoplasty was performed, with the thinned glans penis retained as a neocervix. The patient received regular follow-up care, which included three negative Papanicolaou smears between 1993 and 1996.

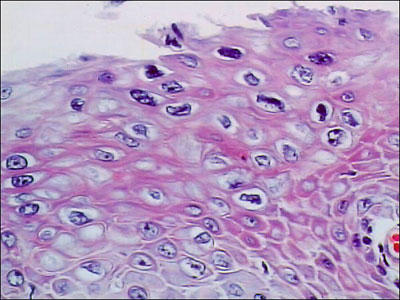

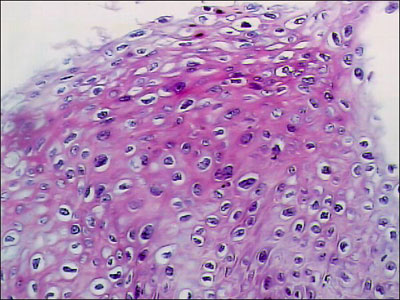

In 1997, a routine Papanicolaou smear taken from the neocervical area revealed changes typical of human papillomavirus (HPV), and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade I (VAIN I). Subsequent culposcopy with 5% acetic acid demonstrated two acetowhite areas, consistent with HPV effect, on the neocervix and on the lateral wall of the vagina. On biopsy, the neocervical area showed vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia, grade II (VAIN II) (Figures. 1 and 2). Biopsies of the lateral wall area showed only mild atypia. The patient was treated with surgical resection of the neocervical area; this was performed with biopsy forceps due to vaginal stenosis. These excisional biopsy specimens showed VAIN I.

Figure 1: Initial excisional biopsy of the neocervix, showing dysplastic changes (VAIN II); magnification x160

Figure 2: Initial excisional biopsy of the neocervix, showing marked nuclear atypia; magnification x400

Frequent follow-up examinations were recommended, but the patient was

not seen again until one year later, when she presented with complaints of

vaginal pain and dyspareunia. A Papanicolaou smear of the neocervix showed

only inflammatory changes. Repeat culposcopy with 5% acetic acid revealed

only atrophic vaginitis; no dysplastic lesions were present. Her atrophic

vaginitis responded to estrogen cream. Despite reassurance, she remained

anxious about the implications of her positive cytology and biopsy results.

This is the first published case report of neovaginal neoplasia in a MtF transsexual. It should remind clinicians that periodic surveillance for cancer of the neovagina is indicated in this population. It also raises the question of whether routine cytological screening for vaginal cancer should be part of that surveillance. Until better data are available, it is only possible to draw some inferences, based on the experiences of related populations. It may be useful to consider vaginal cancer in natal women with natural vaginas, and in women with neovaginas secondary to congenital vaginal agenesis.

Vaginal cancer in natal women with natural vaginas

In natal women with natural vaginas, both primary invasive vaginal carcinoma and VAIN are rare. The incidence of primary vaginal carcinoma in the US female population is only 0.3 per 100,000 (Fetters et al, 1996). The peak incidence is in the fifth to seventh decades, with half of cases occurring in patients over the age of 60 in one large series (Herbst et al, 1970). In contrast to cervical carcinoma, where intraepithelial neoplasia is three times more common than invasive carcinoma, primary invasive vaginal carcinoma is two to three times more common than VAIN (Hilborne and Fu, 1987).

Like other lower anogenital tract cancers, both invasive vaginal carcinoma and VAIN are strongly associated with HPV exposure, especially with HPV 16 and 18 (Strickler et al, 1998). While VAIN can progress to invasive carcinoma, this is uncommon. Aho and colleagues (1991) followed 23 patients with VAIN for 3 years or longer, without treatment. Progression to invasive vaginal carcinoma occurred in only two cases (9%); VAIN persisted in three cases (13%), and regressed in 18 cases (78%).

An annual Papanicolaou smear of the cervix is recommended to screen for cervical carcinoma in women who have not undergone hysterectomy, or who have a history of abnormal cervical cytology. However, its role in cancer surveillance for women who have undergone hysterectomy for benign disease is less clear. The sensitivity of vaginal cytological smears is low; they may miss over one-third of vaginal cancers (Bell at al, 1984). Moreover, the false positive rate of vaginal smears is high. Fischer et al (1995) estimated that fewer than 1% of women with a positive vaginal smear cytology following hysterectomy for benign disease would be found to have vaginal carcinoma, using worst-case assumptions. Under more realistic assumptions, the true-positive rate may be only 0.05% (Fetters et al, 1996). This lack of sensitivity and specificity, combined with the rarity of primary vaginal carcinoma, limits the value of vaginal cytology as a screening tool.

These observations have led several authorities to discourage routine cytological screening following hysterectomy for benign disease. Piscitelli et al (1995) recommended a Pap smear only every ten years for such women. Other authorities have not recommended any routine vaginal cytological screening in women without a cervix, unless there is prior history of neoplasia (Canadian Task Force on Cervical Cancer Screening Programs, 1982; U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, 1996; Pearce et al, 1996; Fetters et al, 1996; Noller, 1996). This situation would seem to be analogous to that of MtF transsexuals following vaginoplasty.

Neovaginal cancer in women with congenital vaginal agenesis

There have been at least 16 published case reports of neovaginal carcinoma in women who have undergone vaginoplasty for congenital vaginal agenesis (see Table 1). These comprise eight squamous cell carcinomas, five adenocarcinomas, one mucinous adenocarcinoma, and two cases of intraepithelial neoplasia (carcinoma in situ). While this may seem like a large number of cases, congenital vaginal agenesis is not an especially rare condition. The estimated incidence is one in every 4000 to 5000 births (Bobin et al, 1999). Since it is likely that a significant percentage of women with congenital vaginal agenesis have undergone vaginoplasty, 16 case reports of neovaginal neoplasia over the course of 70 years probably reflects a very low underlying incidence of disease. HPV exposure is thought to be a risk factor for neovaginal carcinoma, as it is for other anogenital cancers (Baltzer and Zander, 1989).

Table 1: Neovaginal Neoplasia after Vaginoplasty for Vaginal Agenesis

|

Case |

Reference |

Age

at |

Type

of |

Age

at |

Type

of |

|

1 |

Ritchie (1929)

|

13 |

small bowel segment |

26 |

adenocarcinoma |

|

2 |

Lavand Homme (1938) |

18 |

colon segment |

33 |

adenocarcinoma |

|

3 |

Jackson (1959)

|

17 |

skin graft |

25 |

squamous cell |

|

4 |

Krieg (1966)

|

27 |

colon segment |

71 |

adenocarcinoma |

|

5 |

Cali (1968)

|

18 |

skin graft |

26 |

squamous cell |

|

6 |

Duckler (1972) Stefanoff (1973) |

17 |

skin graft |

36 |

squamous cell |

|

7 |

Rotmensch (1983) |

28 |

skin graft |

33 |

squamous cell |

|

8 |

Jaeger (1984)

|

28 |

colon segment |

52 |

adenocarcinoma |

|

9 |

Rummel (1985)

|

17 |

skin graft |

29 |

squamous cell (in situ) |

|

10 |

Imrie (1986)

|

17 |

skin graft |

29 |

squamous cell (in situ) |

|

11 |

Hopkins (1987)

|

18 |

skin graft |

42 |

squamous cell |

|

12 |

Baltzer (1989)

|

28 |

skin graft |

43 |

squamous cell |

|

13 |

Auber (1989) Borruto (1990) |

20 |

small bowel segment |

59 |

adenocarcinoma |

|

14 |

Balik (1992)

|

19 |

peritoneal graft |

38 |

squamous cell |

|

15 |

Munkarah (1994)

|

21 |

skin graft |

42 |

mucinous adenocarcinoma |

|

16 |

Bobin (1999)

|

22 |

cleavage w/ ingrowth |

43 |

squamous cell |

It is not clear that vaginal neoplasia in women with neovaginas follows the same pattern as in women with natural vaginas. The average age at time of diagnosis of the sixteen reported patients with neovaginal neoplasia was only 39 years; and their average interval from vaginoplasty to diagnosis was only 19 years. The invasive carcinomas in these patients were nearly always symptomatic, with vaginal bleeding being the most common clinical presentation. Vaginal cytological screening played essentially no role in the detection of the invasive carcinomas.

Nevertheless, the combination of relatively young age and sometimes-short interval to diagnosis in these patients led Hopkins and Morley (1987) to suggest that women with neovaginas should undergo routine cytological screening as well as regular pelvic examinations throughout their lifetimes. They did not suggest how frequently screening should be done. Lelle et al (1990) and Takashina et al (1988) also recommended periodic cytological screening, at unspecified intervals. All these recommendations were made prior to the widespread reconsideration of routine cytological screening that occurred in the mid-1990s.

Vaginoplasty technique and the risk of vaginal cancer

There is no convincing evidence that vaginoplasty technique affects the subsequent risk of neovaginal carcinoma. Neoplasia has been reported following vaginoplasty using skin grafts (Cases 3, 5-7, 9-12, 15), small bowel segments (Cases 1, 13), colon segments (Cases 2, 4, 8), peritoneum (Case 14), or ingrowth of skin following simple cleavage (Case 16).

Several observers have noted the tendency of vaginal graft tissues to assume the histological features of normal vaginal mucosa, regardless of their origin (Lelle et al, 1990; Takashina et al, 1988; Bleggi-Torres et al, 1997). Nevertheless, in the neovaginal carcinomas thus far reported, the cell type of the neoplasm has generally reflected the type of tissue used to line the neovagina. The ten published cases of squamous cell carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia developed followed skin grafts (eight cases), a peritoneal graft (one case), or simple cleavage with skin in-growth (one case). The five cases of adenocarcinoma followed bowel segment vaginoplasties. The possible exception to this pattern is the lone case of mucinous adenocarcinoma, which followed a skin graft vaginoplasty; however, it occurred in association with a chronic recto-vaginal fistula, raising the possibility that the carcinoma originated in a remnant of the fistula tract.

Lebovic and colleagues (1999) observed that squamous cell cancer had never been reported following rectosigmoid vaginoplasty, and therefore concluded that this technique offered an advantage over skin graft vaginoplasty. While their observation may be technically accurate, it is misleading. Carcinomas have in fact developed following colon segment vaginoplasties (Lavand Homme, 1938; Krieg and Goltner, 1966; Jaeger and Engel, 1984); but these have been adenocarcinomas, rather than squamous cell carcinomas.

The neocervix as a risk factor for vaginal cancer

In the present case, the neocervix created from the glans penis was the

location at which intraepithelial neoplasia was detected. This raises the

question of whether the penile glans might have greater potential for the

development of neovaginal carcinoma than other penile skin. There is

suggestive evidence that this may indeed be the case.

Squamous cell carcinomas, which account for 95% of penile cancers, usually

occur on the glans or prepuce; only 2% of such carcinomas occur on the

penile shaft (Burgers et al, 1992). Penile cancer is rare in populations

that practice infant circumcision, which facilitates better hygiene of the

glans. However, the peak incidence of penile cancer is in the seventh

decade (Griffiths and Mellon, 1999), suggesting a long incubation period.

Carcinoma in situ of the penile glans is much more likely to progress to

invasive carcinoma than is carcinoma in situ of the skin of the penile

shaft (Micali et al, 1996). These observations suggest that the glans may

be especially prone to carcinomatous change, relative to the skin of the

penile shaft. Like primary vaginal carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma of

the penis is also associated with HPV exposure, especially HPV types 16

and 18.

Recently, there has been an increasing tendency for surgeons performing male-to-female sex reassignment to use the penile glans to construct a neoclitoris, rather than a neocervix (Fang et al, 1992; Eldh, 1993; Perovic, 1993; Rubin, 1993; Hage and Karim, 1996; Rehman and Melman, 1999). This technique has the advantage of locating the glans in a position where it can be more easily examined for possible dysplastic or carcinomatous changes, in addition to its other benefits.

Negative consequences of routine cytological screening in MtF transsexuals

Even though routine cytological examination in MtF transsexuals might not be demonstrably beneficial, it could be defended on the grounds that it plausibly detects some carcinomas while having few negative consequences. However, this ignores the costs of routine testing, as well as the expense, inconvenience, and anxiety associated with follow-up examinations after false-positive cytological results.

Cost considerations may not seem particularly salient in the case of MtF

transsexuals, because such individuals are so few in number. Even if every

MtF transsexual underwent annual cytological screening post-vaginoplasty,

the total cost would admittedly be low. However, many MtF transsexuals

lack health insurance coverage for conditions related to their

transsexuality. They may have to pay out of pocket for screening

procedures, as well as for follow-up of positive results -- the vast

majority of which are likely to be false positives. This puts a special

responsibility on providers to choose such tests wisely.

The more important negative consequences of routine screening are likely

to be the inconvenience and anxiety associated with positive cytological

results, even if such results are ultimately determined to be false

positives (Fischer et al, 1995; Noller, 1996). These adverse effects are

difficult to quantify, but they can sometimes be significant, as in the

present case.

Male-to-female transsexuals who have undergone vaginoplasty should receive annual pelvic examinations to screen for pelvic cancer, but there is no evidence to suggest that they would benefit from vaginal cytological screening in most cases. Invasive vaginal carcinoma following vaginoplasty appears to be quite rare. Intraepithelial neoplasia that might not be detected on routine pelvic examination appears to be even rarer, and is unlikely to progress to invasive disease. The vast majority of positive cytological results in MtF transsexuals are likely to be false positives, and follow-up testing in these cases will cause unnecessary expense, inconvenience, and worry.

However, in patients who have undergone penile inversion vaginoplasty with

the glans penis retained as a neocervix, routine cytological examination

of the neocervix may be indicated. The glans appears to be more prone to

carcinomatous change than the skin of the penile shaft, and

intraepithelial neoplasia of the glans is more likely to progress to

invasive carcinoma than is intraepithelial neoplasia of other penile skin.

These factors make regular cytological examination of the glans-derived

neocervix a reasonable practice in MtF transsexuals.

Aho, M., Vesterinen, E., Meyer B., Purola, E., and Paavonen, J. (1991) Natural history of vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia. Cancer, 68(1): 195-197.

Auber, G., Carbonara, T., di Bonito, L., and Patriarca, S. (1989) Carcinoma of the neovagina following a Baldwin-Mori operation for congenital absence of the vagina. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 10(1): 67-68.

Balik, E., Maral, I., Sozen, U., Bezircioglu, I., Tugsel, Z., and Velibese, S. (1992) Karzinom in einer Davydov-neovagina. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 52(1): 68-69.

Baltzer, J. and Zander, J. (1989) Primary squamous cell carcinoma of the neovagina. Gynecologic Oncology, 35(1): 99-103.

Bell, J., Sevin, B., Averette, H., and Nadji, M. (1984) Vaginal cancer after hysterectomy for benign disease: value of cytologic screening. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 64(5): 699-702.

Bleggi-Torres, L., Werner, B., and Piazza, M. (1997) Ultrastructural study of the neovagina following the utilization of human amniotic membrane for treatment of congenital absence of the vagina. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research, 30(7): 861-864.

Bobin, J., Zinzindohoue, C., Naba, T., Isaac, S., and Mage, G. (1999) Primary squamous cell carcinoma in a patient with vaginal agenesis. Gynecologic Oncology, 74(2): 293-297.

Borruto, F. and Ferraro, F. (1990) Adenocarcinoma of a neovagina constructed according to the Baldwin-Mori technique. European Journal of Gynaecologic Oncology, 11(5): 403-405.

Burgers, J., Badalament, R., and Drago, J. (1992) Penile cancer. Clinical presentation, diagnosis, and staging. Urology Clinics of North America, 19(2): 247-256.

Cali, R. and Pratt, J. (1968) Congenital absence of the vagina. Long-term results of vaginal reconstruction in 175 cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 100(6): 752-763.

Canadian Task Force on Cervical Cancer Screening Programs (1982) Cervical cancer screening programs: summary of the 1982 Canadian task force report. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 127(7): 581-589.

Duckler, L. (1972) Squamous cell carcinoma developing in an artificial vagina. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 40(1): 35-38.

Eldh, J. (1993) Construction of a neovagina with preservation of the glans penis as a clitoris in male transsexuals. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 91: 895-900.

Fang, R.-H., Chen, C.-F., and Ma, S. (1992) A new method for clitoroplasty in male-to-female sex reassignment surgery. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 89(4): 679-682.

Fetters, M., Fischer, G., and Reed, B. (1996) Effectiveness of vaginal Papanicolaou smear screening after total hysterectomy for benign disease.JAMA, 275(12): 940-947.

Fischer, G., Fetters, M., and Ruffin, M. (1995) Vaginal smears after hysterectomy. Journal of Family Practice, 41(1): 16.

Griffiths, T. and Mellon, J. (1999) Human papillomavirus and urological tumours: I. Basic science and role in penile cancer. BJU International, 84(5): 579-586.

Hage, J. and Karim, R. (1996) Sensate pedicled neoclitoroplasty for male transsexuals: Amsterdam experience in the first 60 cases. Annals of Plastic Surgery, 36: 621-624.

Harry Benjamin International Gender Dysphoria Association (1998) The Standards of Care for Gender Identity Disorders, Dusseldorf: Symposion Publishing.

Herbst, A., Green, T., and Ulfelder, H. (1970) Primary carcinoma of the vagina. An analysis of 68 cases. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(2): 210-218.

Hilborne, L. and Fu, Y. (1987) Intraepithelial, invasive and metastatic neoplasms of the vagina. In Wilkinson, E. (Ed.), Pathology of the Vulva and Vagina, New York: Churchill Livingston, pp. 181-207.

Hopkins, M. and Morley, G. (1987) Squamous cell carcinoma of the neovagina. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 69(3 Pt 2): 525-527.

Imrie, J., Kennedy, J., Holmes, J. and McGrouther, D. (1986) Intraepithelial neoplasia arising in an artificial vagina. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 93(8): 886-888.

Jackson, G. (1959) Primary carcinoma of an artificial vagina. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 14(4): 534-536.

Jaeger, K. and Engel, C. (1984) Karzinom in kunstlicher scheide bei kongenitaler vaginalaplasie. Der Krankenhausartz, 57: 491-493.

Kirk, S. (1999) You and your gynecologist: will my neo-vagina fool my gynecologist? Transgender Tapestry, 86: 15-16.

Krieg, H. and Goltner, E. (1966) Primares Karzinom in einer künstlichen Scheide. Zentralblatt für Gynäkologie, 88(46): 1575-1578.

Lavand Homme, P. (1938) Complication tardive apparue au niveau d'un vagin artificiel. Bruxelles Medical, 19: 14-15.

Lebovic, G., Laub, D., Laub. D., Oberhelman, H., and Van Maasdam, J. (1999) Construction of a "natural" vagina using rectosigmoid transplantation. In Ehrlich, R. and Alter, G. (Eds.), Reconstructive and Plastic Surgery of the External Genitalia, New York: W. B. Saunders, pp. 258-261.

Lelle, R., Heidenreich, W. and Schneider, J. (1990) Cytologic findings after construction of a neovagina using two surgical procedures. Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, 170(1): 21-24.

Micali, G., Innocenzi, D., Nasca, M., Musumeci, M., Ferrau, F., and Greco, M. (1996) Squamous cell carcinoma of the penis. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 35(3 Pt 1): 432-451.

Munkarah, A., Malone, J., Budev, H., and Evans, T. (1994) Mucinous adenocarcinoma arising in a neovagina. Gynecologic Oncology, 52(2): 272-275.

Noller, K. (1996) Screening for vaginal cancer. New England Journal of Medicine, 335(21): 1599-1600.

Pearce, K., Haefner, H., Sarwar, S., and Nolan, T. (1996) Cytopathological findings on vaginal Papanicolaou smears after hysterectomy for benign gynecologic disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 335(21): 1559-1562.

Perovic, S. (1993) Male to female surgery: a new contribution to operative technique. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 91(4): 703-711.

Piscitelli, J., Bastian,. L., Wilkes, A., and Simel, D. (1995) Cytologic screening after hysterectomy for benign disease. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology,1173(2): 424-430; discussion 430-432.

Rehman, J. and Melman, A. (1999) Formation of neoclitoris from glans penis by reduction glansplasty with preservation of neurovascular bundle in male-to-female gender surgery: functional and cosmetic outcome.Journal of Urology, 161: 200-206.

Ritchie, R. (1929) Primary carcinoma of the vagina following a Baldwin reconstruction operation for congenital absence of the vagina. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 18: 794-799.

Rotmensch, J., Rosenshein, N., Dillon, M., Murphy, A., and Woodruff, J. (1983) Carcinoma arising in the neovagina: case report and review of the literature. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 61(4): 534-536.

Rubin, S. (1993) Sex reassignment surgery male to female. Scandinavian Journal of Urology and Nephrology Supplement. 154: 1-28.

Rummel, H., Kuhn, W., and Heberling, D. (1985) Karzinomentstehung in der neovagina nach vaginalplastik. Geburtshilfe und Frauenheilkunde, 45(2): 124-125.

Steffanoff, D. (1973) Late development of squamous cell carcinoma in a split-skin graft lining a vagina. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 51(4): 454-456.

Strickler, H., Schiffman, M., Shah, K., Rabkin, C., Schiller, J., Wacholder, S., Clayman, B., and Viscidi, R. (1998) A survey of human papillomavirus 16 antibodies in patients with epithelial cancers. European Journal of Cancer Prevention, 7(4): 305-313.

Takashina, T., Kanda, Y., Tsumura, N., Hayakawa, O., Tanaka, S., and Ito, E. (1988) Postoperative changes in vaginal smears after vaginal reconstruction with a free skin graft. Acta Cytologica, 32(1): 109-112.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (1996) Guide to Clinical Preventive

Services, 2nd ed., Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins.

I wish to thank Joy Shaffer M.D. and John Benecki P.A. for reviewing the

manuscript.

Correspondence and requests for materials to

Anne Lawrence, M.D.

1812 East Madison Street, Suite 102,

Seattle, WA 98122

e-mail: alawrence@mindspring.com